by Alison Richards , NPR

A Halloween apple bob may seem as homespun as a hayride, but that shiny red apple has a steamy past. It was once a powerful symbol of fertility and immortality.

Apple bobbing and eating candy apples are "the fossilized remnants of beliefs that ultimately go back to prehistory," British apple expert and fruit historian, Joan Morgan, tells the Salt.

Morgan and I co-wrote The New Book of Apples several years back. I asked her this week for a refresher on the fruit's Halloween-specific tricks and treats.

Throughout Europe, Morgan says, "apples, apple peels and even pips have long been used to peer into the romantic future." And when early European colonists brought the first apple trees to North America as seeds — also known as pips — in their pockets, these customs came with them.

Bobbing for apples was one of them. In one popular version of the game, girls would secretly mark apples before tipping them into a barrel of water. Apples float, and as the girls' potential sweethearts ducked to catch the fruit with their teeth, future couplings were determined — or foretold.

Girls also continued the tradition of using apple peels to divine their romantic destiny. Every fall, communities in New England would prepare mountains of apples for the great kettles of apple butter that were put up for the winter. An eligible young lady would try to peel an apple in a single unbroken strip, toss the peel over her shoulder, and peer nervously to see what letter the peel formed on the floor: This was the initial of her future husband.

But, as Morgan emphasizes, the playful connection between apples and courtship reflects a more serious and ancient link between apples, fertility and a life without end.

"Apples once grew wild across western Asia and Europe and were regarded as sacred across many cultures," Morgan says. Early Indo-European mythologies tell of goddesses "like the Norse Idun, who dispenses magical apples to her fellow deities to keep them young."

Avalon, where the dying King Arthur is said to have been laid to rest, is an "Isle of Apples," Morgan recalls, and "the Irish hero Bran is beckoned to his paradise by a branch of apple blossom from Emain Ablach, an island in a marvelous archipelago beyond the sea, where apple trees bloom and fruit at the same time."

It's not hard to imagine how apples became such powerful symbols of fertility and renewal. As the leaves turned, and the days shortened, the arrival of apples on the menu of hunter-gatherers and the first farmers would have been eagerly anticipated. It didn't really matter whether the apples were large or small, sweet or sour. They could be eaten fresh, boiled or baked; strung up to dry for the winter months; or allowed to ferment into a hard cider that must have made the dark and cold easier to bear.

In the failing autumn light, a shiny red or golden apple might have seemed like a promise — or an entreaty — that the sun would come again. Apple blossoms heralded the renewal of life each spring. And in the magical mix of image and meaning, ripe apples acquired the power and allure of a fertile woman's body.

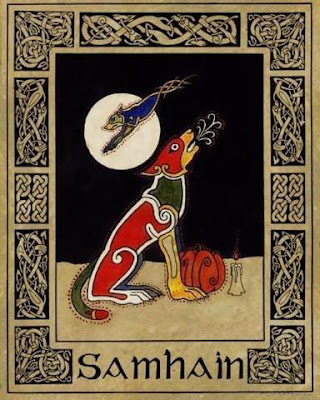

The specific connection between apples, fortune-telling and Halloween goes back to the Celtic festival Samhain. It fell around the end of our modern October, and marked the end of summer, the end of harvest and — revelers worried — perhaps the extinction of life itself.

To encourage the sun deity to return the following year, ancient Celts burned huge bonfires into the night and tied apples to evergreen branches. Gifts of fruit and nuts, and animal sacrifices were offered to the gods.

According to this tradition, barriers to the Underworld were temporarily suspended to allow the year's dead to enter. But this liminal state also allowed ghosts and mischievous spirits to visit the living. It was a time when divination was supposedly especially powerful.A Halloween apple bob may seem as homespun as a hayride, but that shiny red apple has a steamy past. It was once a powerful symbol of fertility and immortality.

Apple bobbing and eating candy apples are "the fossilized remnants of beliefs that ultimately go back to prehistory," British apple expert and fruit historian, Joan Morgan, tells the Salt.

Morgan and I co-wrote The New Book of Apples several years back. I asked her this week for a refresher on the fruit's Halloween-specific tricks and treats.

Throughout Europe, Morgan says, "apples, apple peels and even pips have long been used to peer into the romantic future." And when early European colonists brought the first apple trees to North America as seeds — also known as pips — in their pockets, these customs came with them.

Bobbing for apples was one of them. In one popular version of the game, girls would secretly mark apples before tipping them into a barrel of water. Apples float, and as the girls' potential sweethearts ducked to catch the fruit with their teeth, future couplings were determined — or foretold.

Girls also continued the tradition of using apple peels to divine their romantic destiny. Every fall, communities in New England would prepare mountains of apples for the great kettles of apple butter that were put up for the winter. An eligible young lady would try to peel an apple in a single unbroken strip, toss the peel over her shoulder, and peer nervously to see what letter the peel formed on the floor: This was the initial of her future husband.

But, as Morgan emphasizes, the playful connection between apples and courtship reflects a more serious and ancient link between apples, fertility and a life without end.

"Apples once grew wild across western Asia and Europe and were regarded as sacred across many cultures," Morgan says. Early Indo-European mythologies tell of goddesses "like the Norse Idun, who dispenses magical apples to her fellow deities to keep them young."

Avalon, where the dying King Arthur is said to have been laid to rest, is an "Isle of Apples," Morgan recalls, and "the Irish hero Bran is beckoned to his paradise by a branch of apple blossom from Emain Ablach, an island in a marvelous archipelago beyond the sea, where apple trees bloom and fruit at the same time."

It's not hard to imagine how apples became such powerful symbols of fertility and renewal. As the leaves turned, and the days shortened, the arrival of apples on the menu of hunter-gatherers and the first farmers would have been eagerly anticipated. It didn't really matter whether the apples were large or small, sweet or sour. They could be eaten fresh, boiled or baked; strung up to dry for the winter months; or allowed to ferment into a hard cider that must have made the dark and cold easier to bear.

In the failing autumn light, a shiny red or golden apple might have seemed like a promise — or an entreaty — that the sun would come again. Apple blossoms heralded the renewal of life each spring. And in the magical mix of image and meaning, ripe apples acquired the power and allure of a fertile woman's body.

The specific connection between apples, fortune-telling and Halloween goes back to the Celtic festival Samhain. It fell around the end of our modern October, and marked the end of summer, the end of harvest and — revelers worried — perhaps the extinction of life itself.

To encourage the sun deity to return the following year, ancient Celts burned huge bonfires into the night and tied apples to evergreen branches. Gifts of fruit and nuts, and animal sacrifices were offered to the gods.

|

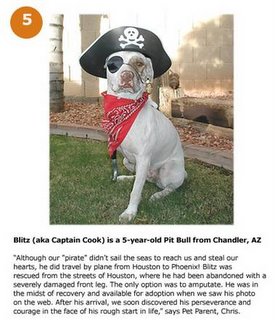

In 1886, Irish Halloween celebrations included bobbing for apples. |

The Romans and then the Christian Church hijacked Samhain and grafted on their own celebrations, but many elements endure.

And as for those candy apples? That's a more recent invention. "It's claimed they were invented accidentally in 1908 by William Kolb a candy maker in Newark, N.J.," says Morgan. "He dropped some apples in his candy syrup" and in a region with plenty of fruit trees — and a sugar refinery — a new Halloween tradition was born.

.jpg)